This article was prompted by a post in one of the scleroderma focused Facebook support groups that I am active in. The poster indicated that she had read an article that said that internal organ involvement occurred in the first 7 years and was asking about this. I see posts like this all the time where patients are wondering if or when they might get internal organ involvement with their particular variant of scleroderma.

This article was prompted by a post in one of the scleroderma focused Facebook support groups that I am active in. The poster indicated that she had read an article that said that internal organ involvement occurred in the first 7 years and was asking about this. I see posts like this all the time where patients are wondering if or when they might get internal organ involvement with their particular variant of scleroderma.

First, some brief background. The word “scleroderma” literally means hard skin. Scleroderma is a name for a family of diseases where skin changes are a common symptom or potential symptom. There are two main types of scleroderma: localized and systemic. Localized variants of scleroderma include diseases such as morphea or linear scleroderma and are pretty much restricted to the skin with no internal organ involvement. In contrast, systemic scleroderma includes diseases often referred to as “limited scleroderma” (used to be referred to as CREST syndrome) or “diffuse scleroderma”. In most cases, when someone uses the word “scleroderma”, they are referring to systemic scleroderma rather than the localized forms.

So what does it mean to have “limited scleroderma” or “diffuse scleroderma”? There is a LOT of confusion around these diagnoses, especially with the term “limited scleroderma”. The full names for these two diseases are actually “limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis” (abbreviated lcSSc in the research literature) and “diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis” (abbreviated dcSSc in the research literature). Patients often think that word “limited” means that their disease is limited to the skin, which is definitely not the case (unlike localized scleroderma which IS limited to the skin). What “limited” actually refers to is the fact that with the limited variants of scleroderma (most commonly associated with anticentromere antibodies but sometimes with Th/To antibodies), the pattern of skin changes is less extensive (i.e., “limited”) than in the diffuse variants of systemic scleroderma, where skin changes can occur anywhere on the body. With limited variants of systemic scleroderma, skin changes are typically limited to the fingers and lower arms, toes and lower legs, and the face.

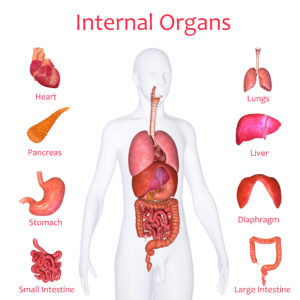

But the real key here is the word “systemic” as part of the terms “limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis” and “diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis”. Systemic scleroderma is initially a disease of the microvascular system: it starts with damage to the smallest blood vessels. The rest of the eventual symptoms, including skin changes, lung or heart problems, damage to the GI tract, kidney problems, etc., result from continued vascular damage and other processes including immune system activation and fibrosis (scarring).

What this means is that from the very beginning, if you develop one of the systemic variants of scleroderma, you DO have internal organ involvement. That is what is meant by “systemic”. Often this involvement is only microscopic (seen when tissue is examined under a microscope) but not symptomatic. Systemic scleroderma is often, but not always, a steadily progressive disease. The rate of progression varies widely based on the particular type of scleroderma and the individual patient. For example, with diffuse variants of scleroderma, skin thickening develops rapidly in the first few years but then slows down, sometimes with noticeable skin improvement. It is not clear why this happens. But internally, damage can nevertheless continue.

The key question is whether or not the internal organ damage reaches the point where it causes clinical problems. To illustrate: patients with limited scleroderma often live relatively normal lifespans, but with increasing symptoms and potential disability over the years. Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) is one of the most dangerous complications for patients with limited scleroderma. It turns out that if you monitor lung functioning in patients with limited scleroderma over time, it is common to see a gradual decline in some key laboratory measures of breathing function. Only 15% to 25% of patients with limited scleroderma are ever diagnosed with PAH. The rest of the patients never reach diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis of PAH even though they may have impaired lung functioning. Some may have clinical symptoms such as shortness of breath upon exertion but others may never have problems like this at all. In these cases, lung functioning may be impaired without having any effect on the patient’s quality of life.

In summary, systemic scleroderma IS “systemic” in that it does involve damage to internal organs, but in many cases, the damage to an organ may never be serious enough to result in clinical symptoms. This is one of the reasons why your doctors monitor you closely with diagnostic tests. The goal is to identify any “functional” internal problems early when it is easier to treat them.