Scleroderma (literally “hard skin”) is an umbrella term for a family of rare diseases with the common factor being abnormal thickening (fibrosis) of the skin. However, not everyone with scleroderma develops skin changes. With some variants of the disease, skin changes usually occur early in the disease process and can develop very rapidly. With other forms of scleroderma, skin changes may not occur for many years after the development of other symptoms and in rare cases may never be a significant symptom of the disease.

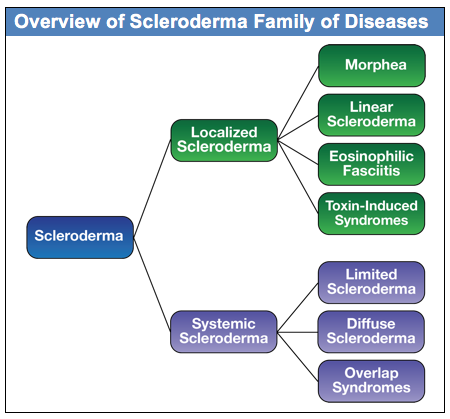

There are two main groupings of the scleroderma family of diseases: Localized and Systemic, as shown in the diagram below:

The focus of this document is on the systemic forms of scleroderma, although basic information is included on the localized forms. The localized forms of scleroderma are limited to different kinds of skin changes and do not have internal organ involvement. In contrast, the systemic forms of scleroderma (frequently referred to as systemic sclerosis or SSc in research literature), are complex autoimmune diseases that can affect organs throughout the body in addition to skin changes.

Within the systemic forms of scleroderma, there are three major categories of the disease: diffuse, limited and overlap syndromes. The more rapidly progressing forms of systemic scleroderma are in a category called diffuse scleroderma. In research literature, this is referred to as diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis and is commonly abbreviated as dcSSc. This form of systemic scleroderma is typically characterized by rapid development of skin thickening, beginning with the hands and face and extending to the arms and trunk. People with diffuse scleroderma are at greater risk for developing internal organ involvement early in the disease process. The specific internal organ systems that are affected depends to some degree on which specific type of diffuse scleroderma the patient has, as indicated by the patient’s antibody profile.

The second major category of systemic scleroderma is called limited scleroderma. The word “limited” refers to the fact that the skin involvement in this form of systemic scleroderma is usually limited to the lower arms and legs and sometimes the face. There is still significant internal organ involvement with limited scleroderma, but it generally develops more slowly than with the diffuse form. In research literature, this is referred to as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and is commonly abbreviated as lcSSc. It is worth noting that this form of scleroderma used to be referred to as CREST Syndrome, and you will still find many articles that use the older term. The name CREST is an acronym derived from the syndrome’s five most prominent symptoms:

C Calcinosis, painful calcium deposits in the skin

R Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal blood flow in response to cold or stress, often in the fingers

E Esophageal dysfunction, reflux (heartburn), difficulty swallowing caused by internal scarring

S Sclerodactyly, thickening and tightening of the skin on the fingers and toes

T Telangiectasia, red spots on the hands, palms, forearms, face and lips

While limited scleroderma progresses more slowly and has a better overall prognosis than diffuse scleroderma, different variants of limited scleroderma (based on antibody profile) have different complication risks over the long term.

The third category of systemic scleroderma is a diverse group that is generally referred to as scleroderma overlap syndromes. With overlap syndromes, while patients have clear scleroderma specific symptoms, they also have symptoms that overlap with other autoimmune diseases, including lupus and myositis (muscle inflammation). An example is Mixed Connective Tissue Disorder, which includes symptoms that are common in scleroderma, lupus, and myositis. The specific antibody determines the nature of the overlap syndrome.